Introduction

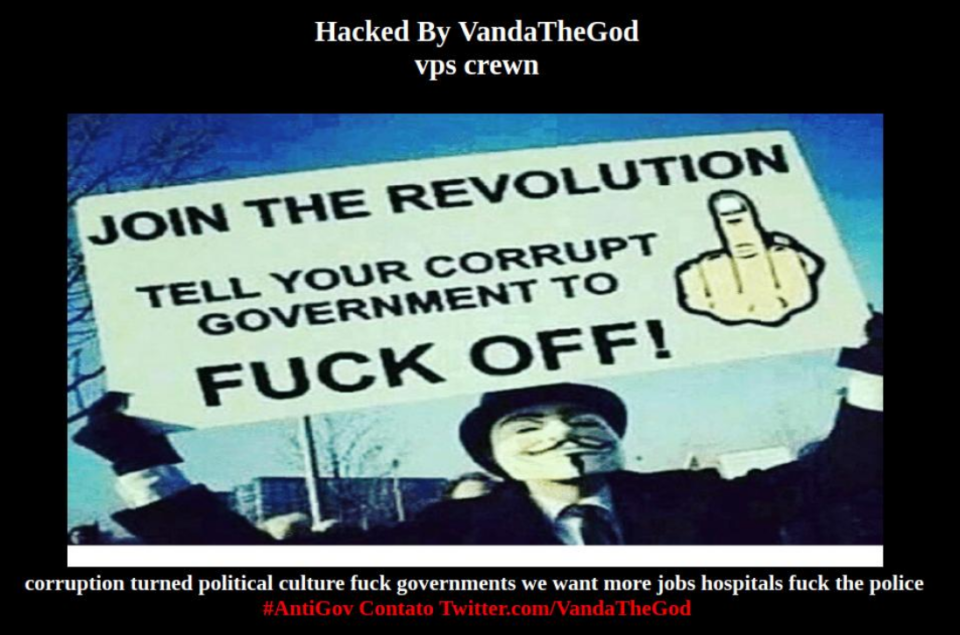

Since 2013, many official websites belonging to governments worldwide were hacked and defaced by an attacker who self-identified as ’VandaTheGod.’

The hacker targeted governments in numerous countries, including: Brazil, the Dominican Republic, Trinidad and Tobago, Argentina, Thailand, Vietnam, and New Zealand. Many of the messages left on the defaced websites implied that the attacks were motivated by anti-government sentiment, and were carried out to combat social injustices that the hacker believed were a direct result of government corruption.

Although the websites’ defacement gave VandaTheGod a lot of attention, the attacker’s activity extended beyond that, to stealing credit card details and leaking sensitive personal credentials.

However, by closely examining those attacks, we were able to map VandaTheGod’s activity over the years, and eventually uncover the attacker’s real identity.

Social Media Activity

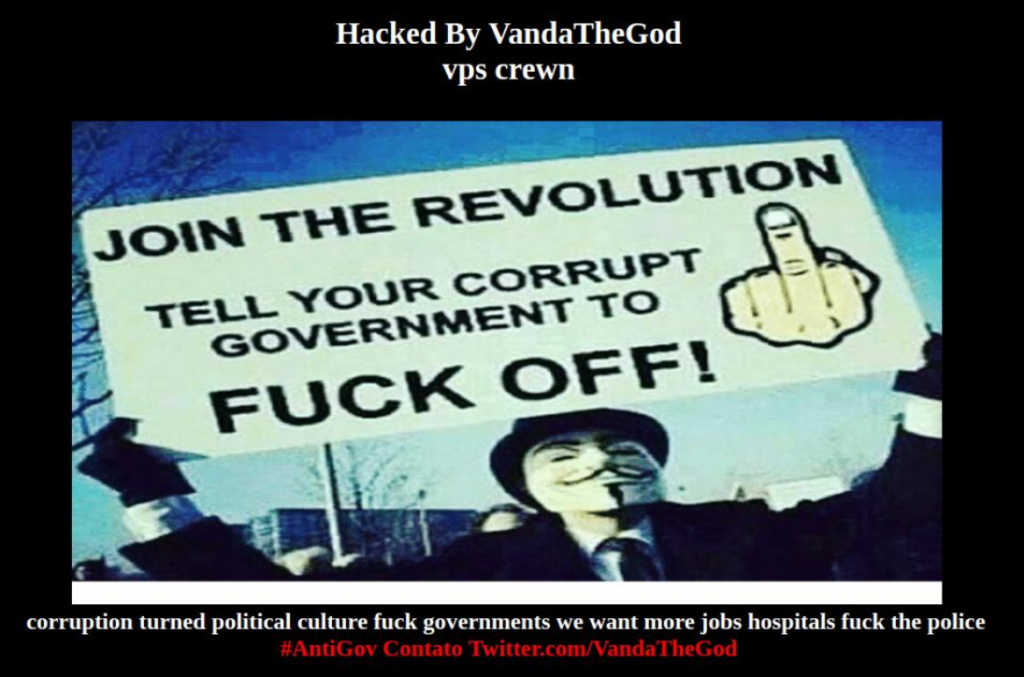

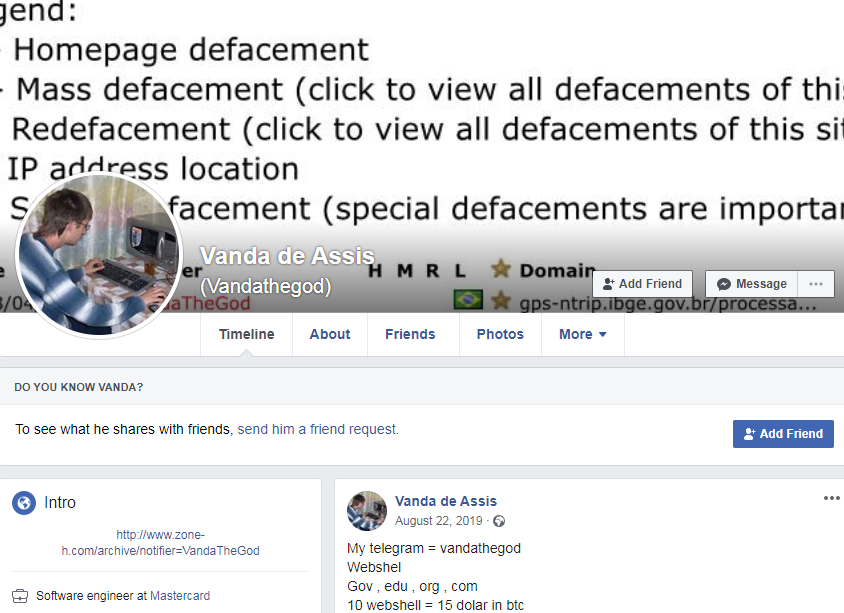

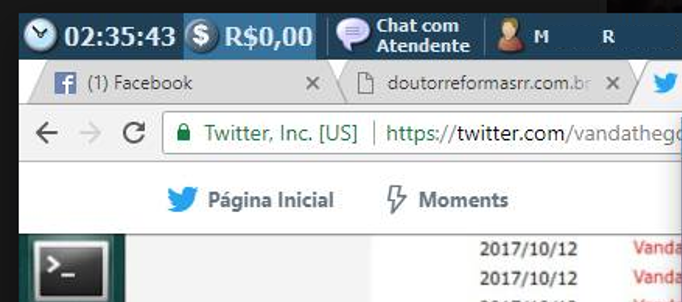

The person behind the ‘VandaTheGod’ persona operated under multiple aliases in the past, such as ’Vanda de Assis’ or ’SH1N1NG4M3’, and was highly active on social media, primarily Twitter. They would often share the results of those hacking endeavors with the public:

A link to this Twitter account would sometimes even be added to the message VandaTheGod left on compromised websites, confirming that this profile was indeed managed by the attacker.

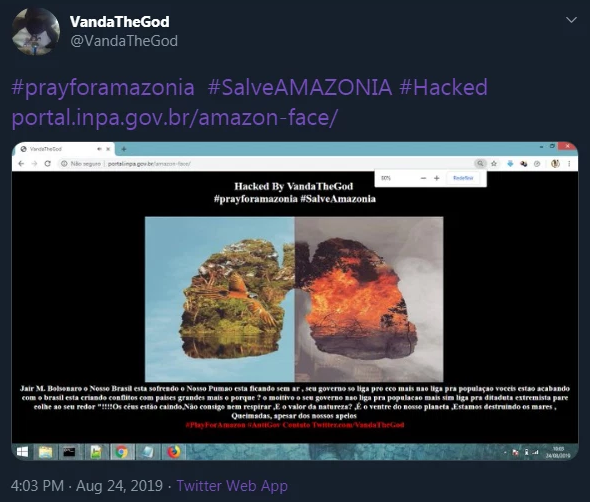

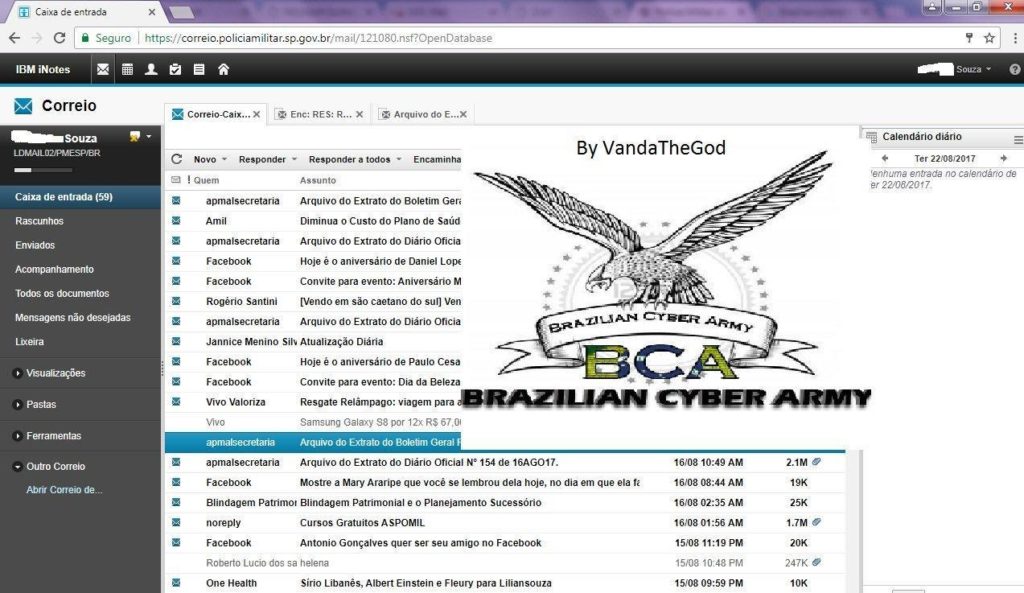

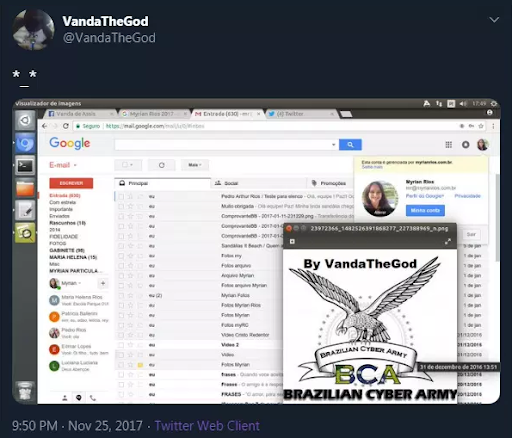

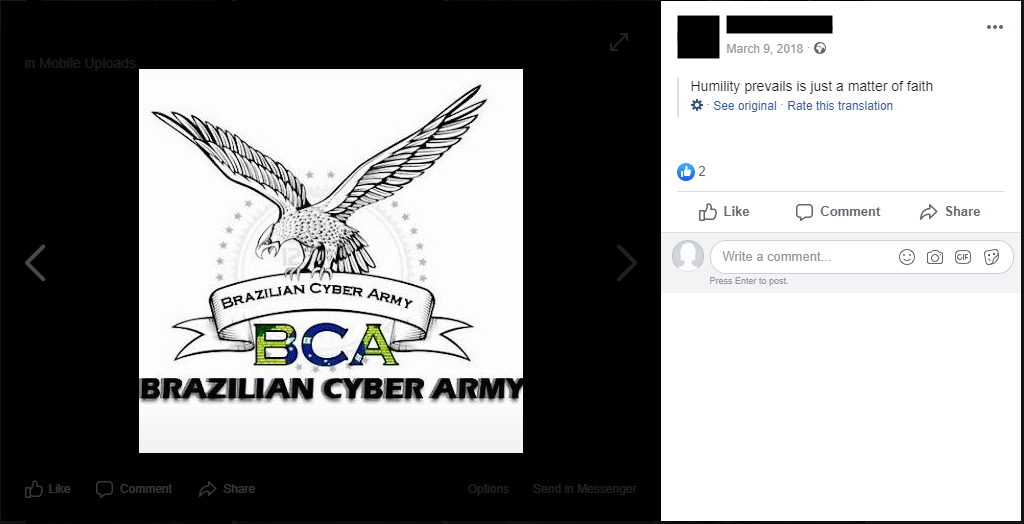

Many of the tweets in this account were written in Portuguese. In addition, the attacker claimed to be a part of the “Brazilian Cyber Army” or “BCA”, often displaying BCA’s logo in screenshots of compromised accounts and websites:

Hacktivism or just hacking?

VandaTheGod didn’t just go after government websites, but also launched attacks against public figures, universities, and even hospitals. In one case, the attacker claimed to have access to the medical records of 1 million patients from New Zealand, which were offered for sale for $200:

While public reports of hacking activity might sometimes deter an attacker from going after new targets, in this case the person appeared to enjoy the attention and would often boast about the reports mentioning VandaTheGod’s accomplishments. They even uploaded some of the media coverage videos to the VandaTheGod YouTube channel.

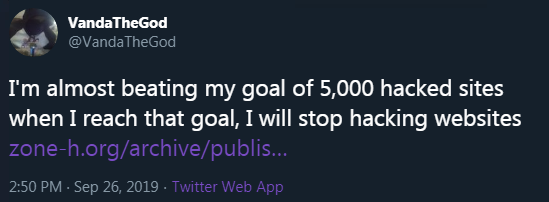

Most of VandaTheGod’s attacks against governments were politically motivated, but a closer look at some of tweets shows the attacker also trying to achieve a personal goal: hacking a total of 5,000 websites.

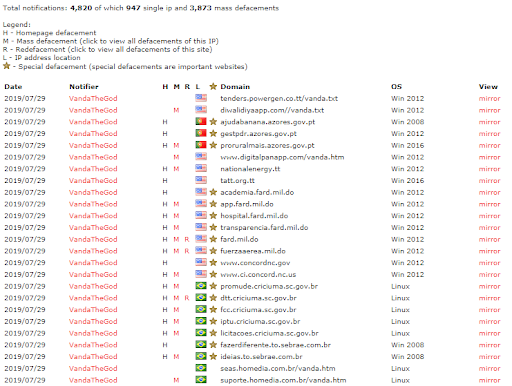

According to zone-h records (a service which records incidents of defaced websites), this goal was nearly reached, as there are currently 4,820 records of hacked websites linked to VandaTheGod. While most of these websites were hacked by mass scanning the internet for known vulnerabilities, the list also includes numerous government and academic websites, which VandaTheGod seems to have deliberately selected.

Getting behind the mask

VandaTheGod’s major role in several hacking groups, as well as their love of publicity, meant that they stayed in touch with others in the hacking community through numerous social media accounts, backup accounts in case of takedown, email addresses, websites and more. Through the years, this activity left a long trail of information for us to investigate.

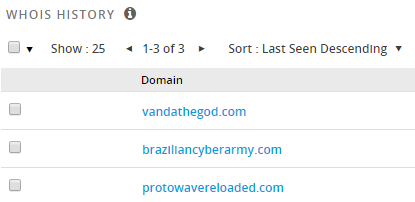

For example, the WHOIS record for VandaTheGod[.]com showed that the website was registered to an individual from Brazil, more specifically from Uberlandia, using the e-mail address fathernazi@gmail[.]com. As it happens, in the past VandaTheGod claimed to be a member of the UGNazi hacking group.

This e-mail address was used to register additional websites, such as braziliancyberarmy[.]com:

However, this was not the only instance where the details shared online by VandaTheGod gave away valuable information about the attacker’s identity. For example, the following screenshot shows the compromised email account of Brazilian actress and TV presenter Myrian Rios:

However, the screenshot also shows an open Facebook tab with the name “Vanda De Assis”, and looking that name up led us to a profile belonging to the attacker:

While this profile did not share any details about the real identity of VandaTheGod, we were able to see many similarities between this and the Twitter accounts operated by the attacker, as the same content was often shared on both platforms:

What was more interesting, however, was that the above screenshot revealed the name of a user that we will identify here only by initials: M. R.

At first we were unsure if M. R. was VandaTheGod’s real initials, but we decided it was worth investigating, as a first name with these initials also appeared in several screenshots shared in VandaTheGod’s Twitter as the username of the machine used for this hacking activity.

At first, we tried searching Facebook for people named M.R., but as expected, we were presented with too many possibilities to fully explore.

Our breakthrough came when we searched for M.R. in conjunction with the city we previously observed in vandathegod[.]com’s WHOIS information: “UBERLANDIA”

This still gave us numerous Facebook profiles, but we were able to locate a single account, which contained an uploaded image endorsing the Brazilian Cyber Army.

At this point, we knew that we were on the right track. All that was left for us to do was to connect this individual’s account with one of the known VandaTheGod’s accounts.

We were able to locate several cross-posts between the newly discovered profile and Vanda de Assis’s Facebook account.

Finally, we located shared photos of the same surroundings from different angles, specifically, the poster’s living room. This confirmed that both the M.R. and VandaTheGod accounts are controlled by the same individual.

Notifying law enforcement

Check Point reported these findings to the relevant law enforcement. All of the detailed social media profiles still exist, but many of the photos in the attacker’s personal profile that overlap with those shared by the VandaTheGod alias were later deleted. Moreover, the activity on these profiles came to a halt toward the end of 2019, and the person has not posted any updates since.

Conclusion

Since 2013, VandaTheGod’s hacking activity has been targeting governments, corporations and individuals alike. They defaced government websites, sold corporate information and dumped many individuals’ credit card information online.

While many tend to underestimate defacement hacking groups as merely digital vandals writing slogans on websites, VandaTheGod has proven with numerous successful attacks against reputable websites, that hacktivism often crosses a line into further criminal activity, such as credentials and payment-card theft, and indeed share their exploits and techniques with the wider cyber-crime community – making them a very real danger to online security. .

VandaTheGod succeeded in carrying out many hacking attacks, but ultimately failed from the OPSEC perspective, as he left many trails that led to his true identity, especially at the start of his hacking career. Ultimately, we were able to connect the VandaTheGod identity with high certainty to a specific Brazilian individual from the city of Uberlândia, and relay our findings to law enforcement to enable them to take further action.

Appendix

The table enclosed presents the number of hacked websites, per country, in the time frame between May2019-May2020 according to h-zone records.

| Country | #Hacked Websites |

| USA | 612 |

| Australia | 81 |

| Netherlands | 56 |

| Italy | 53 |

| South Africa | 38 |

| Canada | 33 |

| Germany | 33 |

| Thailand | 28 |

| United Kingdom | 20 |

| Portugal | 16 |

| Switzerland | 14 |

| Norway | 13 |

| Spain | 9 |

| Belgium | 8 |

| Iran | 8 |

| Romania | 7 |

| Vietnam | 6 |

| Cyprus | 5 |

| Czech Republic | 4 |

| Denmark | 4 |

| France | 3 |

| Ireland | 3 |

| Kenya | 3 |

| Sweden | 3 |

| Chile | 2 |

| Colombia | 2 |

| European Union | 2 |

| Hong Kong | 2 |

| Indonesia | 2 |

| Israel | 2 |

| Malta | 2 |

| Bhutan | 1 |

| Cape Verde | 1 |

| Ethiopia | 1 |

| Greece | 1 |

| Guatemala | 1 |

| Iceland | 1 |

| Luxembourg | 1 |

| Singapore | 1 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 1 |